While studies on the longevity of long COVID support the need to fast-track the development of interventions and therapies to prevent and/or cure the condition, it’s important to prevent reinfections to reduce the future burden of long COVID. Burnet Institute Director and CEO Professor Brendan Crabb AC, and Burnet Chief Health Officer Associate Professor Suman Majumdar, write for The Conversation.

Around 5–10 percent of people who get infected with SARS-CoV-2 will experience symptoms that persist way beyond the initial acute period, a clinical syndrome we are learning more about, known widely as long COVID.

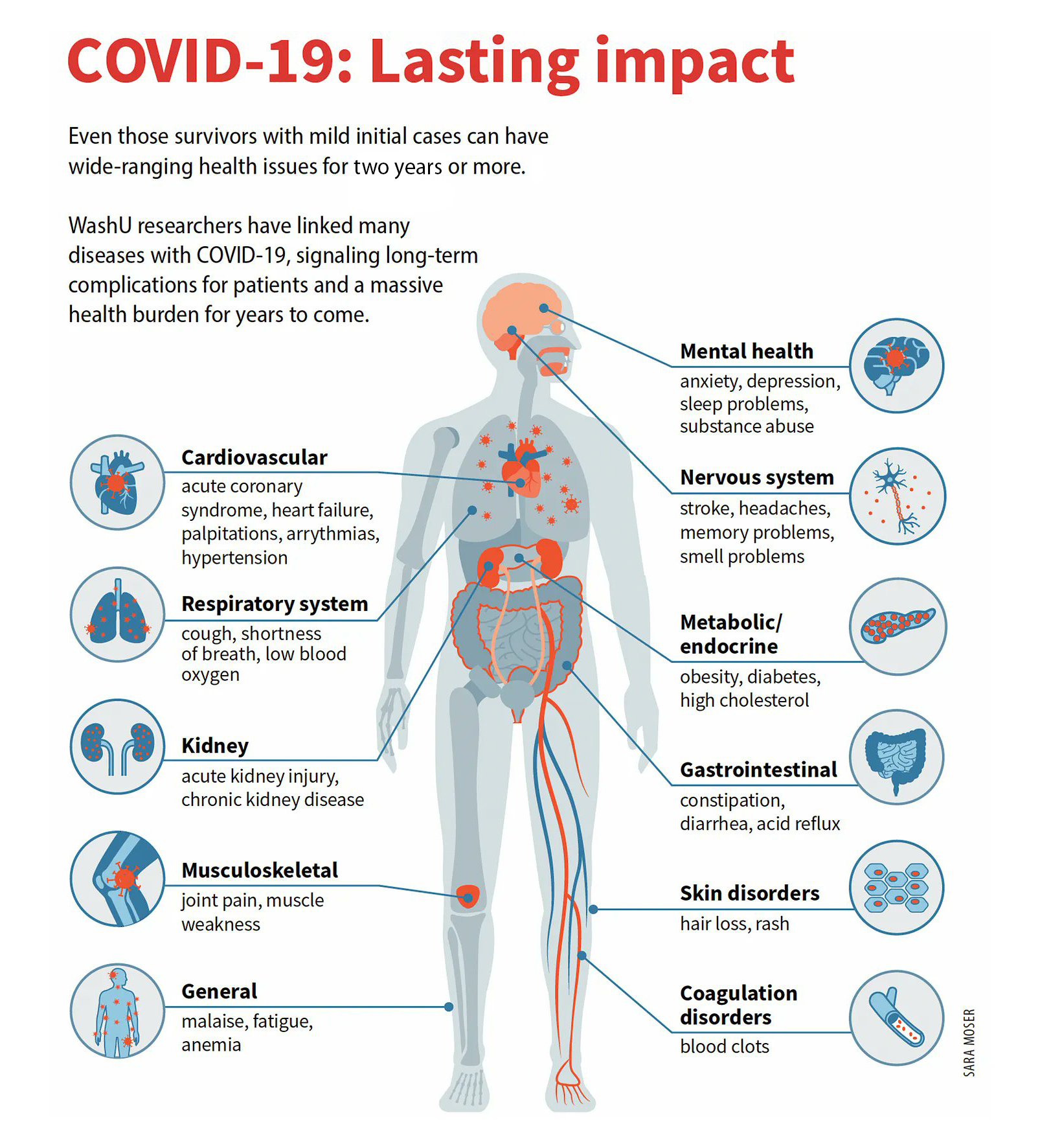

Shortness of breath, brain fog, lethargy and tiredness, loss of smell or taste are common features of long COVID, as is the development of new conditions such as diabetes, heart disease, stroke, depression and dementia.

But how long is the 'long'? If and when do symptoms resolve?

A recent study has examined this in detail, following people for two years after their infection. This and other recently published studies on long COVID show that while symptoms do resolve in many people, their resolution is slow and imperfect.

What did the study find?

The key work, led by Ziyad Al-Aly, examines the effect of SARS-CoV-2 two years after infection in a large group of US veterans. The researchers followed 139,000 people with COVID and almost six million uninfected controls for two years, tracking deaths, hospitalisations and 80 long-term impacts of COVID, categorised into ten organ systems.

They found that people who were initially hospitalised with COVID were 1.3 times more likely to die and 2.6 times more likely to be hospitalised again, compared to the control group (people without COVID), over the two years. After two years, this 'hospitalised' group remained at increased risk of 50 conditions.

People who had milder COVID (who weren’t hospitalised with their initial COVID infection) had an increased risk of death for up to six months and increased risk of hospitalisation for up to 18 months. However, at two years, they remained at increased risk of 25 conditions.

So, while people who were initially hospitalised for COVID had worse outcomes over the two-year follow-up, there was still a substantial burden of illness in people who initially had milder COVID. This included a risk of clots and blood disorders, lung disease, fatigue, gut disorders, muscle and joint disorders and diabetes.

Findings from other recent research were similar

A separate cohort study followed more than 208,000 veterans with COVID over two years. It showed that overall, 8.7 per cent died compared with 4.1 per cent in the uninfected control group. The risk of death was concentrated in the first six months after infection.

A third, not yet peer-reviewed and smaller cohort study of 341 people with long COVID from Spain, found only 7.6 per cent of them recovered at two years.

Another significant (not yet peer-reviewed) study from the United Kingdom assessed diabetes risk after COVID by following 15 million people in England from 2020–21. It found a 30–50 per cent elevated risk of new type 2 diabetes after COVID. This increased risk persisted up to two years. But the risk for type 1 diabetes risk did not persist.

An Australian (not yet peer-reviewed) study followed 31 people who developed long COVID and 31 matched controls who recovered from COVID for two years. It found that most of the concerning immunological dysfunction effects that had been present at eight months, had resolved by two years. While almost two-thirds of those with long COVID (62 per cent) reported improved quality of life over the two years, one-third were still struggling in this regard two years after their infection.

Finally, a recent whole-body positron emission tomography (PET) imaging and biopsy study showed prolonged tissue level immune-activation and viral persistence in the gut for up to a remarkable two years after COVID.

These studies have some limitations

It’s important to note the observational studies have some inherent limitations.

The US veterans cohort studied by Al-Aly is nearly 90 per cent men, with an average age of 61 years, which is different to groups most at risk of long COVID.

They acquired their initial infection in 2020, before Omicron, before vaccination and before therapies – all of which are protective against long COVID to a degree.

Having said that, long COVID still frequently occurs in vaccinated people infected with Omicron.

We still don’t have treatments for long COVID

Increasing understanding about underlying mechanisms of long COVID, such as those involving persistent virus and effects on mitochondria – the powerhouse of the cells - can lead to treatment options that need to be trialled.

In July 2023, the White House established the Office of Long COVID Research and Practice. Two randomised trials are testing whether the antiviral nirmatrelvir-ritonavir (Paxlovid) can treat long COVID are currently recruiting patients.

A separate randomised, placebo-controlled trial has shown that metformin, a commonly prescribed anti-diabetic medication, taken for two weeks (and taken within three days of testing positive for COVID) reduced the chance of developing long COVID by 41 percent. The mechanism may involve an effect on mitochondria or directly on the virus.

But it’s still important to prevent COVID (re)infections

Taken together, these studies on the longevity of long COVID add substantially to the case to fast-track the development of interventions and therapies to prevent and/or cure the condition.

In the meantime, it’s crucially important to prevent (re)infections in the first place to reduce the future burden of long COVID, already estimated to be greater than 65 million people globally.

Breathe clean air by ensuring indoor spaces are well-ventilated. In poorly ventilated or crowded spaces, wear a well-fitted and high-quality mask (a P2, KN95 or N95 mask), and/or use air filtration devices suitable for the space you are in.

Keep up to date with boosters. And get tested so you can get antiviral treatment if you’re eligible.

If you suspect you have long COVID, discuss this with your GP, who may refer you to specialised services or multidisciplinary care.

This article is reproduced from The Conversation. Click here to read the original article.